Hollywood and the Academy:

When two things are the same thing

THE RECENT diversity-related changes by the Board of Governors of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences have delighted a lot of people and enraged as many more. But one consequence of the AMPAS leadership’s announcements on Jan. 22 has been a growing tendency to put rhetorical space between the Academy as an organization and Hollywood as an industry, a collective of creatives making decisions independent of the Academy. This bifurcated mindset got its highest profile of expression at the Producers Guild nominees breakfast in Hollywood on Jan. 23.

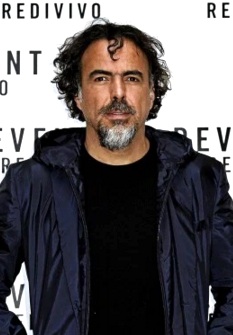

“One of the things that makes this country so powerful is the mixed pot that is the soul of this country, said Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu, the Oscar-winning director of “Birdman” and a strong favorite for a repeat Oscar for “The Revenant.” “And if that is not transmitted on the screen, something is wrong. But The Academy and all the awards are at the end of the chain — change should happen at the beginning of the chain.”

Basil Iwanyk, the producer of “Sicario,” agreed. “As Alejandro said, the Academy does exist at the end of the chain,” he said, “ ... but it’s a big mistake to focus on how the Academy votes instead of focusing on how movies and television are generated. I understand the rage at the Academy. But that’s not the problem. The problem comes much earlier in the process.”

◊ ◊ ◊

The hearts of these two movie professionals couldn’t be more in the right place. But there’s a convenient, disturbing compartmentalization at work in these statements, one that takes comfort with the idea that Hollywood and the Academy are separate entities, independent of each other, at opposite ends of the creative process. In fact, they are anything but.

Steve Pond, the awards columnist at TheWrap, recently reported on the perspective of those sharing this viewpoint.

Pond reported: “Those who’ve applauded and those who’ve criticized the Academy’s initiatives generally agree on one thing: The problem starts not with the Academy, but with the movie industry itself, and until more diverse voices are given positions of power within the studio system, voters will still face a lineup of potential nominees far too heavy on the white male perspective.”

◊ ◊ ◊

BY THEIR thinking, then, the Academy is helpless to influence Hollywood’s production culture, and that regardless of changes to AMPAS membership, the Academy can hardly be responsible for nominating films that aren’t written, produced, financed and distributed by Hollywood.

True, to a point. But by the same token, Hollywood needs the Academy to ratify and confirm (through the Oscar nominations, the Oscar winners, and over the long haul of time) precisely which films should be written, greenlighted, financed, made and distributed. As surely as the Academy is influenced by the films Hollywood anoints with production and distribution, Hollywood is influenced by the Academy, the public prestige it bestows once a year, by the motion picture history it symbolizes every day of the year.

Over generations, both Hollywood and the Academy have gone to great lengths to fortify the idea of their interchangeability (that’s never more true than during Oscar season). For that reason, and in the wake of the current crisis, attempts to rhetorically separate the two are creating a distinction without a difference. Certainly in the public eye.

◊ ◊ ◊

The notion that change in the industry occurs in only one direction, from Hollywood to the Academy, couldn’t be more wrong. The one-direction view reveals a disconnect, an overlooking the inescapable: The films that the Academy honors are exactly the kind of films Hollywood wants to go on producing and distributing. Many of the films that Hollywood makes are exactly the kind of films the Academy has historically honored, and continues to make part of the movie history it celebrates.

It’s not really a chain that Iñárritu and Iwanyk describe, it’s closer to a Möbius strip — something with no beginning or ending, a cycle in which two seemingly separate entities are actually, thoroughly dependent on each other at every stage of the creative process. One in which, on the basis of the public’s perception, they’re one and the same.

And the public perception is the one that really matters. Why? Simple: Because motion pictures aren’t made for Alejandro Iñárritu, Basil Iwanyk, Hollywood or the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. They’re made for the people of the world, and the more of the world’s people who appear in those films, the better.

Image credits: Iñárritu: Rex Shutterstock via Variety.com.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment